Everything you wanted to know about breech birth, but were afraid to ask.

What is the breech position and how common is it closer to term?

Breech presentation is a fetal presentation in which the buttocks are at the opening of the womb. In a frank breech the legs are straight up in front of the body. In a complete breech the legs are folded, but the feet are above the buttocks. In an incomplete breech the feet are below the buttocks (aka “footling breech”).

Breech position is present in 3 to 4 per cent of term pregnancies. Breech positioning is more common prior to term – 25% are breech before 28 weeks, but by 32 weeks only 7% of babies are breech. The vast majority (96%) of breech babies in Australia are now born by planned C-section. Researchers have found that vaginal delivery of breech births in Australia dropped from 23 per cent in 1991 to 3.7 per cent in 2005, in an overwhelming shift towards caesareans.

Why do babies turn to be born? Why is it necessary/important?

It is not an accident of evolution that most babies eventually turn head down for birth. Coming out head first allows the cervix to open to pass the largest part of the baby, and the contractions can gently shape the still-flexible skull to the mother’s pelvis (the skull plates of the foetus, called the fontanelles, are soft and “mold” during birth by folding over each other, enabling the head to fit through the bony pelvis.)

In addition, the head fits neatly against the cervix like an egg in an egg cup. This prevents the umbilical cord from coming down ahead of the baby and getting pinched between the baby and the mother’s pelvis (cord prolapse). For this reason, a very small percentage of breech babies will get into trouble. The mechanics of breech birth also increase the chance of birth injury to the baby.

Why do some babies not turn? What are the theories?

A premature baby is more likely to be breech (as babies grow, gravity and the shape of the uterus together with the baby’s normal movements eventually bring the baby’s head down and keeps her that way. That process hasn’t happened yet in babies who come early).

Another reason is that babies who have something wrong with them are also more likely to be breeches. Babies who are full term, but severely undersized (Intrauterine growth restriction or IUGR) tend to be breech for the same reason as babies born prematurely.

Babies with inborn neuromuscular disabilities also tend to be breech because they don’t engage in the active movements that help the baby end up head down. Certain physical abnormalities such as hydrocephalus (when the baby’s skull is swollen with excessive fluid) predispose to breech as well.

In addition, some babies are in the breech position due to the shape of the mother’s uterus, the amount of amniotic fluid in the uterus and the position of the placenta.

However, a very large percentage of breech babies have no health issues whatsoever.

When should a breech baby be spotted and how?

Breech presentation is diagnosed in late third trimester (from about 34 weeks onwards). It is confirmed either through ultrasound and palpation (manually feeling the mother’s belly and determining the position of the baby)

At what point does a breech baby become a potential issue for giving birth?

Up until about thirty years ago, Australian obstetricians treated breech birth very matter-of-factly and they were expertly trained in the management of vaginal breech birth. Today, vaginal breech delivery is rarely taught to obstetric residents, hence it has become a dying obstetric skill. Added to this, Australia (like the United States) has become a more litigious society and as a result medicine has become more defensive. (An obstetrician would rarely be sued for a breech Caesarean birth that went wrong, but would be wide open to litigation for a breech vaginal birth that went wrong.

It’s important to note that a breech Caesarean delivery is not without risks to both mother and baby. While Caesarean delivery may reduce the risk of birth injury to the baby, Caesarean birth markedly increases maternal risks in both the short and long term over vaginal birth. Caesarean surgery can lead to severe post-partum infections causing prolonged hospital stays, and even (in rare situations) hysterectomy. A Caesarean will leave a woman with a scarred uterus, which will increase her risk of certain placental complications in future pregnancies and may limit her options to deliver vaginally after Caesarean (VBAC) with subsequent babies.

Breech babies born by Caesarean are also at risk for the same complications as a breech vaginal birth (birth injuries such as a broken collarbone, nerve damage etc) and in addition, they are at risk of being cut during the surgery itself.

Babies can turn head down at the very last minute – even during labour. However, for babies that remain in a persistent breech position at full term, a decision needs to be made by the mother and her partner and her caregivers as to the mode of delivery – planned Caesarean or vaginal breech.

A woman’s caregivers must be experienced in delivering breech vaginal babies, which usually means being relatively “hands-off” unless there is a need to assist the baby’s head at the end, whereby forceps or other obstetric manoeuvres can be used if necessary. By far, the biggest fear for medical practitioners is that the baby’s head will get stuck.

The mother should be fully informed of all her options, with clear risks and benefits for both options presented to her, so that she can give proper informed consent. If a woman is not satisfied that she has been presented with balanced options, she should seek a second opinion from another caregiver. She should never be coerced, or worse – forced – into making a decision she is not happy with.

If a baby is breech close to birth, what are the options for trying to turn him or her?

ECV – or External Cephalic Version is the procedure a trained obstetrician will do to turn the baby (version) head down (cephalic) by manipulating her from the outside (external).

ECV – or External Cephalic Version is the procedure a trained obstetrician will do to turn the baby (version) head down (cephalic) by manipulating her from the outside (external).

Around Week 37 of pregnancy, a woman will go to hospital for an outpatient procedure. A preliminary ultrasound is performed to evaluate the baby’s position as well as to record the amount of amniotic fluid and determine the position of the placenta.

A drug (tocolytics) will usually be administered to relax the uterus (and prevent it from contracting during the procedure) but this is not required in order to do the procedure itself.

The baby will be monitored through electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) to keep track of the baby’s heart rate. The practitioner will then try to flip the baby by manipulating her belly. The procedure may be uncomfortable, but it should rarely take more than 5 minutes, many ECV’s take less than one. If the procedure fails, or the baby turns back, some practitioners will try again. EFM is continued for a while after the procedure to ensure that the baby has tolerated the procedure well.

Watch a video of a baby being turned with ECV:

Traditional “ECV” – you might be interested to watch this clip (watch from about 4:00 minutes) from the excellent Australian documentary: The Face of Birth – where a traditional indigenous midwife talks about how she manages labour through rubbing and massaging a mother’s belly to ensure the baby is in a good position for birth. A note at the end of this section states that in 50 years they have never seen a breech baby!)

In an Australian study, only 66% of pregnant women had ever heard of ECV, and most of these women (87%) learned about version from books or family/friends—not from care providers. Only 39% of women in the study said they would choose a version if they had a breech baby and 22% were undecided. Women who did not want a version said that they had concerns about effectiveness and safety for the baby (Raynes-Greenow, Roberts et al. 2004).

Multiple studies agree that ECV is safe and effective when practiced as directed, but that overly forceful manipulations can be extremely dangerous.

What natural alternatives are there to help turn a baby?

There are a range of alternative-medicine techniques which may help to turn a breech baby:

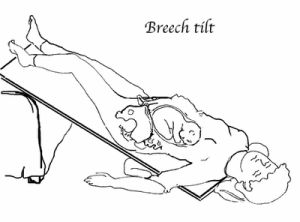

The first (and most simple) method is maternal positioning (or postural techniques). The earlier in pregnancy you begin, the greater the odds of success, because there is more amniotic fluid and the baby is smaller. Unless your caregiver objects, the following positions are worth trying if your baby is still breech at six to eight weeks before your due date:

Pelvic Tilt: Three times a day for 10-15 minutes each time, lie on your back with bent knees and your hips elevated about 30 cms on cushions, or lie on a propped ironing board. Pick times when your baby is active and your bladder is empty. Have someone help you to get in and out of the tilt position. Try to relax and visualise where you want your baby to move to. Placing headphones playing gentle or classical music just above your pubic bone may also coax your baby to move into the direction you want him to go. Your partner could also talk to your baby in the same area. The volume should be comfortable for you, and therefore won’t be too loud for the baby.

Pelvic Tilt: Three times a day for 10-15 minutes each time, lie on your back with bent knees and your hips elevated about 30 cms on cushions, or lie on a propped ironing board. Pick times when your baby is active and your bladder is empty. Have someone help you to get in and out of the tilt position. Try to relax and visualise where you want your baby to move to. Placing headphones playing gentle or classical music just above your pubic bone may also coax your baby to move into the direction you want him to go. Your partner could also talk to your baby in the same area. The volume should be comfortable for you, and therefore won’t be too loud for the baby.

Knee-chest position: Kneel on a mattress with flexed hips and your upper body flat against the mattress. Your thighs should be apart, so that they do not press on your belly. You should try to do this every couple of hours for 15 minutes each time, for 5 days (realistically, this is not so easy – but do your best!)

Moxibustion is a type of Chinese medicine that may be helpful in turning a breech baby. It involves burning a herb close to the skin at an acupuncture point on the little toe to produce a warming sensation. More evidence is needed concerning the benefits and safety of moxibustion. However, when combined with either acupuncture or postural techniques, evidence suggests that moxibustion is safe and increases your chances of turning a breech baby.

We still don’t know for sure which kind of moxibustion method (timing during pregnancy, number of sessions, length of sessions, etc.) works best for turning breech babies. However it appears that using moxibustion twice per day for two weeks (during 33-35 weeks of pregnancy) will work for 1 out of every 8 women.

If women are interested in using Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) (moxibustion and acupuncture) to help turn a breech baby, they should consult a licensed acupuncturist who specializes in treatment of pregnant women.

Rebozo –The rebozo is a traditional Mexican shawl that is long enough to wrap around a woman’s body (about 4-5 feet). The rebozo is a multifunction tool for labour, used to assist the mother into various positions and for relaxation. If you do not own a rebozo, you can substitute with a large scarf, sheet or piece of fabric. The small jiggling motions of the rebozo, or sifting, increases flexibility in the broad ligament and abdominal muscles supporting the womb helping baby to flip on his or her own. The sensation is gentle and relaxing, almost as if you are rocking your baby from side to side from the outside. An experienced doula (professional birth attendant) can help you to do this. While there haven’t been studies that have tested the effectiveness of the rebozo for turning a breech baby, anecdotally, many women report positive outcomes. The rebozo has also been used traditionally for generations.

Webster Technique – The Webster Technique is a specific chiropractic technique that reduces interference to the nerve system and balances maternal pelvic muscles and ligaments. This in turn reduces torsion in the uterus, a cause of intra-uterine constraint of the baby and allows for optimal fetal positioning in preparation for birth.” (ICPA).

As yet, there have not been any large scale randomised controlled trials testing the efficacy of this technique, although there has been some anecdotal evidence to suggest it can be effective.

What is the most effective method of turning a baby?

As a Lamaze Certified Childbirth Educator, I ensure that the information I pass on to clients is evidence-based and not opinion-based.

Given the current evidence available, I would advise a woman whose baby is in a breech position at around 34 weeks, to start using postural techniques daily (unless her caregiver advises otherwise), together with moxibustion and acupuncture administered by a licensed Traditional Chinese Medicine practitioner who specialises in working with pregnant women.

If the baby has not turned by 37 weeks, I would advise her to seek out an experienced obstetrician who has a high success rate of ECV and have the procedure done. Hopefully the baby will turn and she should keep up the postural techniques afterwards to ensure baby stays in a cephalic (head down) position until labour begins.

What does a breech position mean for birth? Is a C-section the only option?

As mentioned earlier, 30 years ago, a baby in a breech position at full term was dealt with very matter-of-factly, and was not a reason to go to C-section automatically. An article that was published in 2000 in the prestigious UK medical journal, The Lancet, had a considerable influence on changing that protocol as it suggested that caesarean sections posed fewer risks to breech babies than vaginal births. But many doctors have criticised the findings of the study, arguing its methods were flawed, and saying there is strong evidence that vaginal breech births are safe in certain circumstances. Slowly, we are starting to see the pendulum swinging back and an increased effort to train new doctors in the skills required to deliver a breech baby vaginally. However, most women will still be told that they require a C-section if there is breech at term.

Because adverse breech outcomes among healthy, mature infants are so rare, it would take thousands of cases to show whether routine Caesarean is better. Individual trials of vaginal breech haven’t been large enough to draw conclusions. Pooling together all the quality data available though, it seems that the death rate for planned vaginal birth calculates as 1 baby per 1,000. To put this statistic into perspective, fetal loss rates from amniocentesis, another situation where the mother’s interest counterbalances the baby’s, fall in the same range.

As for mothers, the same studies showed that about 1:1000 will experience serious complications following a vaginal birth, compared with 2:1000 mothers who had a planned Caesarean – so clearly, having a planned Caesarean does not eliminate serious health risk for the mother.

Under what circumstances can a woman have a vaginal birth when the baby is breech?

The ideal breech birth candidate is a woman carrying a full-term, or near full-term baby of average size in the frank breech position, that is, the baby’s bottom down and with legs in pike position.

Frank breech is by far the most common type of breech. With a frank breech, the buttocks are about the size of the head, which minimises the possibility that the cervix will dilate enough to pass the body, but not the head, and the chance of the umbilical cord coming down ahead of the baby (prolapsing) is the same as head-down babies.

The mother should also have normal to ample pelvic measurements (N.B. this is not the measurement of her hips!) Pelvic measurements can only be obtained from doing an X-ray called pelvimetry, although this is not without risk as the baby will be exposed to radiation from the X-ray and the X-ray also does not account for other factors such as positioning, or epidural which can both affect the ability of a woman to push out her baby. A CT scan is safer as the radiation levels are significantly lower than X-ray.

Naturally, in addition, the woman must ensure that she is cared for during her labour by physicians and midwives who are experienced in vaginal breech birth.

Does the type of breech position come into account and make a difference when deciding how to proceed/whether a mother can birth vaginally?

Definitely. Everyone agrees that babies who are “stargazers” (that is, babies with heads tipped back – hyperextended neck), should be planned Caesarean sections. These babies can be gravely injured during vaginal birth. In addition, babies with known physical abnormalities should also be Caesarean deliveries.

Heads Up: The Disappearing Art of Vaginal Breech Delivery

“Why are most physicians no longer offering vaginal breech delivery? Fear of liability? Peer pressure? Bullying by insurance companies? Or were they just never taught how?

The documentary film Heads Up: The Disappearing Art of Vaginal Breech Delivery (produced by prenatal chiropractor Dr. Elliot Berlin, DC) answers these questions. As aging doctors skilled in vaginal breech delivery cease to practice, the vaginal option for breech birth is disappearing at a rapid rate. Will doctors who don’t have these skills explain the benefits and risks of both vaginal breech birth and cesarean breech birth to their patients?

The way you birth is your choice. It’s your right. Do not allow a physician to take that away. Research your options so that you can make informed decisions and consents based on facts and evidence.”

Heads Up features several women confronted with the disappearance of this option for their breech babies. Through their personal accounts and the perspectives of medical professionals, Heads Up explores this widely misunderstood subject and the need to restore this lost art and lost option. — headsupfilm.com

Are there any other resources can I read?

- Breech Birth Australia & New Zealand (also has a Facebook group)

- Spinning Babies – an excellent website that will teach you about optimal fetal positioning and show you natural techniques to help turn your breech baby

- Learn about the Webster Technique

- Evidence Based Birth has two excellent articles on breech birth:

- Article 1

- Article 2

- Belly Belly – includes a list of doctors across Australia who support vaginal breech birth

- Check out these amazing photos of a breech baby being born vaginally

- The stunning featured image in this blog was taken by Brazilian photographer, Line Sena.

Tanya Strusberg is a Lamaze Certified Childbirth Educator (LCCE) and founder of birthwell birthright, an independent childbirth education practice based in Melbourne. In 2015, Tanya was inducted as an FACCE (Fellow of the Academy of Certified Childbirth Educators) in recognition of her significant contribution to childbirth education. Through her internationally-accredited Lamaze Educator Training program, she is very excited to be training a new generation of Australian Lamaze educators.

Last, but absolutely not least, she is also the mum of two beautiful children, her son Liev and daughter Amalia.